Sight – Sound – Scent – Shade

Caroline Stone, Friday 1 October 1982

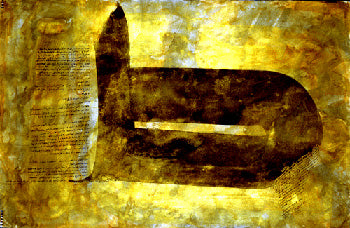

The picture on the left was taken by Ali Omar Ermes of the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan.

Since the time of the Prophet, Muslim gardeners have attempted to create an earthly paradise to praise God and please man’s senses. The Quran presents some wonderful images of gardens with beautiful trees and running streams to celebrate the magnificence of the Creator. In the afterlife, one of the rewards of the faithful is to rest in these gardens of Paradise, so it is hardly surprising that gardens have long been a favourite occupation throughout the Muslim world.

The art of the garden has developed over the centuries. The basis form of the garden in Muslim Middle East evolved in remote antiquity and was largely dictated by the land and climate. Heat, difficult soil and a scarcity of water ruled out gardens of the kind later favoured by the English, while the formal continental style would have been unbearably hot.

The typical garden, then, was enclosed to protect it from the desert winds. Two streams of water crossed it at a central point, where there might be a brimming pool, the tomb of some great or holy man, a pavilion or, later, a fountain. The streams were often compared to the four rivers of Paradise mentioned in the Quran, and their beds were sometimes lined with tiles, generally blue.

The four quarters might then be further divided by smaller channels, pools and pathways. At the corners would be orange and cypress trees. The flower beds, with carved stone borders, would be laid out with a profusion of ornamental plants, herbs and vegetables.

At one end of the garden, there was sometimes a building, a madrassah, private house or mausoleum. The most famous example of this is the Taj Mahal at Agra, although the gardens there today are much less shady than the originals – the trees have been sacrificed to the view.

This was the layout largely followed in Persia, where the name garden originated. A number of examples have survived, at least in general outline, but few are in good condition. One is the Bagh I Iram at Shiraz, a city once famous for its gardens: the garden is not what it once was, but its cypresses, orange trees, pot plants and roses are still pleasing.

Variations on this basis form soon developed. Some were reduced to the size of a courtyard (as in Andalusia), while others expanded to nearly a mile square (like Tamerlane’s great garden of Dilkusha at Samarkand).

As part of the classical world’s cultural exchange, this type of garden reached Greece and Rome. Later, in the wake of Islam, it spread west to Spain and Morocco (where it still survives) and east to India and Pakistan. There, over the last century, a number of magnificent gardens have been lovingly restored.

Gardens are all too fragile and vanish rapidly if untended. Tomb gardens usually last longer than pleasure gardens, as more provision is made for their upkeep – but even so, it is not surprising that none have survived intact from the early years of Islam. Archaeology is beginning to remedy this, notably in Spain, where the original layouts of gardens have been restored and pollen analysis of the soil has identified the plants that originally grew in them.

The enchanting gardens of the Alcazar in Seville, which once belonged to the palace of Al Mutamid, can still evoke the descriptions of the Arab poets, even though the original design has been overlaid with Renaissance and 19th-century additions. The atmosphere of the Muslim garden is there in the palm and orange trees, watercourses, pools, beds of scented flowers, pavilions and shady walks.

In the Courtyard of the Lions in Granada’s Alhambra and at the Generalife, it is possible to see something of the more compact type of garden – but again, neither garden is in its original form.

One important point that all restorers have ignored, however, is that flower beds were sunk below the level of the paths. While walking, one’s feet were on a level with the flowers, as on a carpet. This arrangement had other advantages: watering could be done from the raised channels, while the plants did not interfere with the architecture. Sometimes the beds were suck so deep that they made underground courtyards – a perfect place to escape the summer heat. Gardens with these sunken beds are still found in Morocco.

The sorts of flowers that grew in these gardens obviously varied from place to place. Al Himyari, writing in Spain in the 11th century CE, noted 20 of the most common plants, including myrtle, white and yellow jasmine, narcissus, daffodil, violet, mauve stock, wallflower, lily, iris, rose, water lily, poppy, camomile, pomegranate and bean flower. Other writers added basil, orange trees, mint, palms and vines to the list.

This is far from being the whole inventory, however. The Andalusians, being passionate gardeners, were so avid for new plants that it is thought that the number of species grown doubled during the 12th century.

To the east, the flowers that could be grown were naturally somewhat different. The Mughal gardens were rich in lotus, pandanus, hibiscus, banana, Budda’s hand citron, silk-cotton tree and numerous other exotic and fragrant species.

Emperor Babur, the second Muslim conqueror of India, described in his diary the problems of introducing plants from his native Central Asia and Kabul to the Indian plains. Babur was a great gardener: his Bagh i Banafsaj, (violent garden) at Kabul was renowned, as was the lotus garden (Bagh i Nilofer) he made at Agra. His diary recorded how he grew grapes at Agra from cuttings sent express from Balkh, and melons from seeds from his beloved Kabul. Babur’s gardens have not survived as well as those of the later Mughals, however. At Shahdara, near Lahore, is Nur Jehan’s garden of Dilkusha (heart’s delight), which she had planted as a pleasure garden for herself and her husband, Emperor Jahangir, who was Babur’s grandson. They now lie buried there, he is the great mausoleum that she designed, and she under a simple slab nearby.

Local tastes always influenced the layout of gardens. The Turks, for example, had a passion for tulips and hyacinths. Central Asians admired the plane tree, and there was hardly a city there (or in northern Iran, Afghanistan or the Punjab) without a Chenar Bagh, or a tree garden.

For their part, the Arabs favoured the palm, which was the best of all trees according to the traditions. The Persians planted whole gardens of roses. In Andalusia, there was a special orange blossom. In North Africa, the scented jasmine was the favourite.

The Muslim garden was designed to satisfy all five senses: the sight of greenery, the scent of flowers, the sound of running water, the taste of fruit and the sensation of coolness and shade.

The gardens were not, however, designed exclusively for pleasure. Often the flower beds were of turf studded with flowers, which was perfect for spreading a prayer carpet. There would be running water or a reflecting pool suitable for performing ablutions. Mosques also had their gardens, usually of water and trees, with benches set out for the older men to rest.

Ironically, gardens abandoned in their prime are easier to reconstruct, for their paths and watercourses were simply overgrown and not altered or deliberately destroyed. The task of reconstruction is, naturally, much simpler when the garden has strong architectural features.

This was the case with a number of dramatic water gardens built in Kashmir and the Himalayan foothills by the Mughal emperors. Literally hundreds of these have vanished. But some, such as the Shalimar in Lahore, the Achabal near Islamabad and the gardens of Lake Dal can still be seen today – and are among the marvels of garden design throughout the world.

The use of pot plants is another notable aspect of the Muslim garden. At least until a few years ago, anyone wandering about a city in Iran, or invited to a private house, might have found a courtyard with a fountain or watercourse, the flowerbeds being entirely composed of pot plants. A similar arrangement can be seen in Andalusian patios.

Such a tactic is very sensible wherever the soil is poor or water-scarce. It means that individual plants can be removed without disturbing the rest and that the devoted gardener can rearrange the pots into a new pattern every day, like the spreading of different carpets. The designs can be very complicated, even calligraphic – forming, for example, the world Bismillah – and can be appreciated only when seen from the upper rooms.

Pot plant gardens, which were more common on upper terraces, are nothing new. An 11th-century traveller mentions the considerable sums spent by wealthy men in Cairo on rare and interesting plants for their rooftops. But the best dry climate gardens are in Khurasan: at dry Fariman, for example, coloured stones from river beds are arranged into gardens extraordinarily like carpets.

But perhaps the oldest and most valuable sort of garden is one that can still be found in many parts of the Muslim world, from Tozeur in southern Tunisia to Qatif on the east coast of Saudi Arabia. These were never intended for pleasure, yet they are the most satisfying kind: under the protective shade of tall palms, there are fruit trees and, below them, vegetables and flowers. Such intense cultivation depends on a scrupulously maintained network of streams, with water often brought up from the earth by artesian wells. Marvellously cool and scented after the heat and dust, this is surely the simplest Quranic image of gardens on this earth and in the after-world.

This article featured in Arabia – The Islamic World Review in Oct 1982, No.14

Leave a comment

Also in ART & CULTURE

2e Édition De Fikra “la Créativité Est Le Pilier De L’entrepreneuriat”

Vincenzo Nesci, l’un des principaux promoteurs de la 2e édition Fikra, lors de cette conférence internationale a abordé «la création d’entreprise et l’entrepreneuriat». Selon le directeur exécutif de Djezzy, ces derniers, «doivent être réalisés dans des conditions d’optimisme et de créativité pour permettre un réel essor dans les domaines commercial, industriel et créatif»