Islamic Medicine: 1,000 Years Ahead of It's Time

Dr. Ibrahim B. Syed is Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40292 and President of the Islamic Research Foundation International http://www.irfi.org

SUMMARY

Within a century after the death of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) the Muslims not only conquered new lands, but also became scientific innovators with originality and productivity. They hit the source ball of knowledge over the fence to Europe. By the ninth century, Islamic medical practice had advanced from talisman and theology to hospitals with wards, doctors who had to pass tests, and the use of technical terminology. The then Baghdad General Hospital incorporated innovations which sound amazingly modern. The fountains cooled the air near the wards of those afflicted with fever; the insane were treated with gentleness; and at night the pain of the restless was soothed by soft music and storytelling. The prince and pauper received identical attention; the destitute upon discharge received five gold pieces to sustain them during convalescence. While Paris and London were places of mud streets and hovels, Baghdad, Cairo and Cardboard had hospitals open to both male and female patients; staffed by attendants of both sexes. These medical centres contained libraries pharmacies, the system of interns, externs, and nurses. There were mobile clinics to reach the totally disabled, the disadvantaged and those in remote areas. There were regulations to maintain quality control on drugs. Pharmacists became licensed professionals and were pledged to follow the physician’s prescriptions. Legal measures were taken to prevent doctors from owning or holding stock. in a pharmacy. The extent to which Islamic medicine advanced in the fields of medical education, hospitals, bacteriology, medicine, anaesthesia, surgery, pharmacy, ophthalmology, psychotherapy and psychosomatic diseases are presented briefly.

INTRODUCTION

Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) who is ranked number one by Michael Hart’, a Jewish scholar, in his book The 100: The Most Influential Persons in History, was able to unite the Arab tribes who had been torn by revenge, rivalry, and internal fights, and produced a strong nation acquired and ruled simultaneously, the two known empires at that time, namely the Persian and Byzantine Empires. The Islamic Empire extended from the Atlantic Ocean on the West to the borders of China on the East. Only 80 years after the death of their Prophet, the Muslims crossed to Europe to rule Spain for more than 700 years. The Muslims preserved the cultures of the conquered lands. However, when the Islamic Empire became weak, most of the Islamic contributions in science were destroyed. The Mongols burnt Baghdad (1258 A.D.) out of barbarism, and the Spaniards demolished most of the Islamic heritage in Spain out of hatred.

The Islamic Empire for more than 1000 years remained the most advanced and civilized nation in the world. This is because Islam stressed the importance and respect of learning, forbade destruction, and developed in Muslims the respect for authority and discipline, and tolerance for other religions. The Muslims recognized excellence and hungering intellectually were avid for the wisdom of the world of Galen, Hippocrates, Rufus of Ephesus, Oribasius, Discorides and Paul of Aegina. By the tenth century, their zeal and enthusiasm for learning resulted in all essential Greek medical writings being translated into Arabic in Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad. Arabic became the International Language of learning and diplomacy. The center of scientific knowledge and activity shifted eastward, and Baghdad emerged as the capital of the scientific world. The Muslims became scientific innovators with originality and productivity. Islamic medicine is one of the most famous and best-known facets of Islamic civilization, and in which the Muslims most excelled. The Muslims were the great torchbearers of international scientific research. They hit the source ball of knowledge over the fence to Europe. In the words of Campbell’ “The European medical system is Arabian not only in origin but also in its structure. The Arabs are the intellectual forebears of the Europeans.”

The aim of this paper is to prove that Islamic Medicine was 1000 years ahead of its times. The paper covers areas such as medical education, hospitals, bacteriology, medicine, anaesthesia, surgery, ophthalmology, pharmacy, and psychotherapy.

MEDICAL EDUCATION

In 636 A.D., the Persian City of Jundi-Shapur, which originally meant beautiful garden, was conquered by the Muslims with its great university and hospital intact. Later the Islamic medical schools developed on the Jundi-Shapur pattern. Medical education was serious and systematic. Lectures and clinical sessions included in teaching were based on the apprentice system. The advice is given by Ali ibnul-Abbas (Haly Abbas: -994 -A.D.) to medical students is as timely today as it was then’. “And of those things which were incumbent on the student of this art (medicine) are that he should constantly attend the hospitals and sick houses; pay unremitting attention to the conditions and circumstances of their intimates, in company with the most astute professors of medicine, and inquire frequently as to the state of the patients and symptoms apparent in them, bearing in mind what he has read about these variations, and what they indicate of good or evil.”

Razi (Rhazes: 841-926 A.D.) advised the medical students while they were seeing a patient bear in mind the classic symptoms of a disease as given in textbooks and compare them with what they found (6).

The ablest physicians such as Razi (Al-Rhazes), Ibn-Sina (Avicenna: 980-1037 A.D.) and Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar: 116 A.D.) performed the duties of both hospital directors and deans of medical schools at the same time. They studied patients and prepared them for student presentation. Clinical reports of cases were written and preserved for teaching’. Registers were maintained.

Training in Basic Sciences

Only Jundi-Shapur or Baghdad had separate schools for studying basic sciences. Candidates for medical study received basic preparation from private tutors through private lectures and self-study. In Baghdad anatomy was taught by dissecting the apes, skeletal studies, and didactics. Other medical schools taught anatomy through lectures and illustrations. Alchemy was once of the prerequisites for admission to medical school. The study of medicinal herbs and pharmacognosy rounded out the basic training. A number of hospitals maintained barbel gardens as a source of drugs for the patients and a means of instruction for the students.

Once the basic training was completed the candidate was admitted as an apprentice to a hospital where, in the beginning, he was assigned in a large group to a young physician for indoctrination, preliminary lectures, and familiarization with library procedures and uses. During this preclinical period, most of the lectures were on pharmacology and toxicology and the use of antidotes.

Clinical training:

The next step was to give the student full clinical training. During this period students were assigned in small groups to famous physicians and experienced instructors, forward rounds, discussions, lectures, and reviews. Early in this period therapeutics and pathology were taught. There was a strong emphasis on clinical instruction and some Muslim physicians contributed brilliant observations that have stood the test of time. As the students progressed in their studies they were exposed more and more to the subjects of diagnosis and judgment. Clinical observation and physical examination were stressed. Students (clinical clerks) were asked to examine a patient and make a diagnosis of the ailment. Only after it had failed would the professor make the diagnosis himself. While performing a physical examination, the students were asked to examine and report six major factors: the patients’ actions, excreta, the nature and location of pain, and swelling and effuvia of the body. Also noted was color and feel of the skin- whether hot, cool, moist, dry, flabby. Yellowness in the whites of the eye (jaundice) and whether or not the patient could bend his back (lung disease) was also considered important (8).

After a period of ward instructions, students were assigned to outpatient areas. After examining the patients they reported their findings to the instructors. After discussion, treatment was decided on and prescribed. Patients who were too ill were admitted as inpatients. The keeping of records for every patient was the responsibility of the students.

Curriculum

There was a difference in the clinical curriculum of different medical schools in their courses; however, the mainstay was usually internal medicine. Emphasis was placed on clarity and brevity in describing a disease and the separation of each entity. Until the time of Ibn Sina the description of meningitis was confused with acute infection accompanied by delirium. Ibn Sina described the symptoms of meningitis with such clarity and brevity that there is very little that can be added after 1000 years 6. Surgery was also included in the curriculum. After completing courses, some students specialized under famous specialists. Some others specialized while in clinical training. According to Elgood (9) many surgical procedures such as amputation, excision of varicose veins and haemorrhoids were required knowledge. Orthopaedics was widely taught, and the use of plaster of Paris for casts after reduction of fractures was routinely shown to students. This method of treating fractures was rediscovered in the West in 1852. Although ophthalmology was practiced widely, it was not taught regularly in medical schools. Apprenticeship to an eye doctor was the preferred way of specializing in ophthalmology. Surgical treatment of cataract was very common. Obstetrics was left to midwives. Medical practitioners consulted among themselves and with specialists. Ibn Sina and Hazi both widely practiced and taught psychotherapy. After completing the training, the medical graduate was not ready to enter practice, until he passed the licensure examination. It is important to note that there existed a Scientific Association which had been formed in the hospital of Mayyafariqin to discuss the conditions and diseases of the patients.

Licensing of Physicians

In Baghdad, in 931 A.D. Caliph Al-Muqtadir learned that a patient had died as the result of a physician’s error. Thereupon he ordered his chief physician, Sinan-ibn Thabit bin Qurrah to examine all those who practiced the art of healing. In the first year of the decree, more than 860 were examined in Baghdad alone. From that time on, licensing examinations were required and administered in various places. Licensing Boards were set up under a government official called Muhtasib or inspector general. The Muhtasib also inspected the weights and measures of traders and pharmacists. Pharmacists were employed as inspectors to inspect drugs and maintain quality control of drugs sold in a pharmacy or apothecary. What the present Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is doing in America today was done in Islamic medicine 1000 years ago. The chief physician gave oral and practical examinations, and if the young physician was successful, the Muhtasib administered the Hippocratic oath and issued a license. After 1000 years licensing of physicians has been implemented in the West, particularly in America by the State Licensing Board in Medicine. For specialists, we have American Board of Medical Specialities such as in Medicine, Surgery, Radiology, etc. European medical schools followed the pattern set by the Islamic medical schools and even in the early nineteenth century, students at the Sorbonne could not graduate without reading Ibn Sina‘s Qanun (Cannon). According to Razi a physician had to satisfy two conditions for selection: firs0y, he was to be fully conversant with the new and the old medical literature and secondly, he must have worked in a hospital as house physician.

HOSPITALS

The development of efficient hospitals was an outstanding contribution to Islamic medicine (7). Hospitals served all citizens free without any regard to their color, religion, sex, age or social status. The hospitals were run by the government and the directors of hospitals were physicians.

Hospitals and separate wards for male patients and female patients. Each ward was furnished with nursing staff and porters of the sex of the patients to be treated therein. Different diseases such as fever, wounds, infections, mania, eye conditions, cold diseases, diarrhea, and female disorders were allocated different wards. Convalescents had separate sections within them. Hospitals provided patients with an unlimited water supply and with bathing facilities. Only qualified and licensed physicians were allowed by law to practice medicine. The hospitals were teaching hospitals for educating medical students. They had housing for students and house-staff. They contained pharmacies dispensing free drugs to patients. Hospitals had their own conference room and expensive libraries containing the most up-to-date books. According to Haddad, the library of the Tulum Hospital which was founded in Cairo in 872 A.D. (I 100 years ago) had 100,000 books. Universities, cities, and hospitals acquired large libraries (Mustansiriyya University in Baghdad contained 80,000 volumes; the library of Cordova 600,000 volumes; that of Cairo 2,000,000 and that of Tripoli 3,000,000 books), physicians had their own extensive personal book collections, at a time when printing was unknown and book editing was done by skilled and specialized scribes putting in long hours of manual labour.

For the first time in history, these hospitals kept records of patients and their medical care.

From the point of view of treatment the hospital was divided into an outpatient department and an inpatient department. The system of the in-patient department differed only slightly from that of today. At tile Tulun hospital, on admission, the patients were given special apparel while their clothes, money, and valuables were stored until the time of their discharge. On discharge, each patient – received five gold pieces to support himself until he could return to work.

The hospital and medical school at Damascus had elegant rooms and an extensive library. Healthy people are said to have feigned illness in order to enjoy their cuisine. There was a separate hospital in Damascus for lepers, while, in Europe, even six centuries later, condemned lepers were burned to death by royal decree.

The Qayrawan Hospital (built-in 830 A.D. in Tunisia) was characterized by spacious separate wards, waiting rooms for visitors and patients, and female nurses from Sudan, an event representing the first use of nursing in Arabic history. The hospital also provided facilities for performing prayers.

The Al-Adudi hospital (built-in 981 A.D. in Baghdad) was furnished with the best equipment and supplies known at the time. It had interns, residents, and 24 consultants attending its professional activities, An Abbasid minister, Ali ibn Isa, requested the court physician, Sinan ibn Thabit, to organize regular visiting of prisons by medical officers (14). At a time when Paris and London were places of mud streets and hovels, Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordova had hospitals which incorporated innovations which sound amazingly modern. It was chiefly in the humaneness of patient care, however, that the hospitals of Islam excelled. Near the wards of those afflicted with fever, fountains cooled the air; the insane were treated with gentleness, and at night music and storytelling soothed the patients.

The Bimaristans (hospitals) were of two types – the fixed and the mobile. The mobile hospitals were transported upon beasts of burden and were erected from time to time as required. The physicians in the mobile clinics were of the same standing as those who served the fixed hospitals. Similar moving hospitals accompanied the armies in the field. The field hospitals were well equipped with medicaments, instruments, tents and a staff of doctors, nurses, and orderlies. The traveling clinics served the totally disabled, the disadvantaged and those in remote areas. These hospitals were also used by prisoners, and by the general public, particularly in times of epidemics.

BACTERIOLOGY

Al-Razi was asked to choose a site for a new hospital when he came to Baghdad. First, he deduced which was the most hygienic area by observing where the fresh pieces of meat he had hung in various parts of the city decomposed least quickly.

Ibn Sina stated explicitly that the bodily secretion is contaminated by the foul foreign earthly body before getting the infection. Ibn Khatima stated that man is surrounded by minute bodies which enter the human system and cause disease.

In the middle of the fourteenth century, “black death” was ravaging Europe and before which Christians stood helpless, considering it an act of God.

At that time Ibn al Khatib of Granada composed a treatise in the defense of the theory of infection in the following way:

To those who say, “How can we admit the possibility of infection while the religious law denies it?” We reply that the existence of contagion is established by experience, investigation, the evidence of the senses and trustworthy reports. These facts constitute a sound argument. The fact of infection becomes clear to the investigator who notices how he who establishes contact with the afflicted gets the disease, whereas he who is not in contact remains safe, and how transmission is effected through garments, vessels, and earrings.

Al-Razi wrote the first medical description of smallpox and measles – two important infectious diseases. He described the clinical difference between the two diseases so vividly that nothing since has been added. Ibn Sina suggested the communicable nature of tuberculosis. He is said to have been the first to describe the preparation and properties of sulphuric acid and alcohol. His recommendation of wine as the best dressing for wounds was very popular in medieval practice. However, Razi was the first to use silk sutures and alcohol for hemostatis. He was the first to use alcohol as an antiseptic.

ANESTHESIA

Ibn Sina originated the idea of the use of oral anaesthetics. He recognized opium as the most powerful mukhadir (an intoxicant or drug). Less powerful anaesthetics known were mandragora, poppy, hemlock, hyoscyamus, deadly nightshade (belladonna), lettuce seed, and snow or ice-cold water. The Arabs invented the soporific sponge which was the precursor of modem anaesthesia. It was a sponge soaked with aromatics and narcotics and held to the patient’s nostrils.

The use of anaesthesia was one of the reasons for the rise of surgery in the Islamic world to the level of an honorable specialty, while in Europe; surgery was belittled and practiced by barbers and quacks. The Council of Tours in 1163 A.D. declared Surgery is to be abandoned by the schools of medicine and by all decent physicians.” Burton stated that “anaesthetics have been used in surgery throughout the East for centuries before ether and chloroform became the fashion in civilized West.”

SURGERY

Al-Razi is attributed to be the first to use the seton in surgery and animal gut for sutures.

Abu al-Qasim Khalaf Ibn Abbas Al-Zahrawi (930-1013 A.D.) known to the West as Abulcasis, Bucasis or Alzahravius is considered to be the most famous surgeon in Islamic medicine. In his book Al-Tasrif, he described hemophilia for the first time in medical history. The book contains the description and illustration of about 200 surgical instruments many of which were devised by Zahrawi himself. In it Zahrawi stresses the importance of the study of Anatomy as a fundamental prerequisite to surgery. He advocates the reimplantation of a fallen tooth and the use of dental prosthesis carved from cow’s bone, an improvement over the wooden dentures worn by the first President of America George Washington seven centuries later. Zahrawi appears to be the first surgeon in history to use cotton (Arabic word) in surgical dressings in the control of hemorrhage, as padding in the splinting of fractures, as vaginal padding in fractures of the pubis and in dentistry. He introduced the method for the removal of kidney stones by cutting into the urinary bladder. He was the first to teach the lithotomy position for vaginal operations. He described tracheotomy, distinguished between goiter and cancer of the thyroid, and explained his invention of a cauterizing iron which he also used to control bleeding. His description of varicose veins stripping, even after ten centuries, is almost like modern surgery. In orthopedic surgery, he introduced what is called today Kocher’s method of reduction of shoulder dislocation and patelectomy, 1,000 years before Brooke reintroduced it in 1937.

Ibn Sina‘s description of the surgical treatment of cancer holds true even today after 1,000 years. He says the excision must be wide and bold; all veins running to the tumor must be included in the amputation. Even if this is not sufficient, then the area affected should be cauterized.

The surgeons of Islam practiced three types of surgery: vascular, general, and orthopedic, Ophthalmic surgery was a specialty which was quite distinct both from medicine and surgery. They freely opened the abdomen and drained the peritoneal cavity in the approved modern style. To an unnamed surgeon of Shiraz is attributed the first colostomy operation. Liver abscesses were treated by puncture and exploration.

Surgeons all over the world practice today unknowingly several surgical procedures that Zahrawi introduced 1,000 years ago.

MEDICINE

The most brilliant contribution was made by Al-Razi who differentiated between smallpox and measles, two diseases that were hitherto thought to be one single disease. He is credited with many contributions, which include being the first to describe true distillation, glass retorts and luting, corrosive sublimate, arsenic, copper sulfate, iron sulphate, saltpeter, and borax in the treatment of disease. He introduced mercury compounds as purgatives (after testing them on monkeys); mercurial ointments and lead ointment.” His interest in urology focused on problems involving urination, venereal disease, renal abscess, and renal and vesical calculi. He described hay-fever or allergic rhinitis.

Some of the Arab contributions include the discovery of itch mite of scabies (Ibn Zuhr), anthrax, ankylostoma and the guinea worm by Ibn Sina and sleeping sickness by Qalqashandy. They described abscess of the mediastinum. They understood tuberculosis and pericarditis.

Al Ash’ath demonstrated gastric physiology by pouring water into the mouth of an anesthetized lion and showed the distensibility and movements of the stomach, preceding Beaumo nt by about 1,000 years. Abu Shal al- Masihi explained that the absorption of food takes place more through the intestines than the stomach. Ibn Zuhr introduced artificial feeding either by gastric tube or by nutrient enema. Using the stomach tube the Arab physicians performed gastric lavage in case of poisoning. Ibn Al-Nafis was the first to discover pulmonary circulation.

Ibn Sina in his masterpiece Al-Quanun (Canon), containing over a million words, described complete studies of physiology, patlhology and hygiene. He specifically discoursed upon breast cancer, poisons, diseases of the skin, rabies, insomnia, childbirth and the use of obstetrical forceps, meningitis, amnesia, stomach ulcers, tuberculosis as a contagious disease, facial tics, phlebotomy, tumors, kidney diseases and geriatric care. He defined love as a mental disease.

OPHTHALMOLOGY

The doctors of Islam exhibited a high degree of proficiency and certainly were foremost in the treatment of eye diseases. Words such as retina and cataract are of Arabic origin. In ophthalmology and optics Ibn al Haytham (965-1039 A.D.) known to the West as Alhazen wrote the Optical Thesaurus from which such worthies as Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci and Johannes Kepler drew theories for their own writings. In his Thesaurus he showed that light falls on the retina in the same manner as it falls on a surface in a darkened room through a small aperture, thus conclusively proving that vision happens when light rays pass from objects towards the eye and not from the eye towards the objects as thought by the Greeks. He presents experiments for testing the angles of incidence and reflection, and a theoretical proposal for magnifying lens (made in Italy three centuries later). He also taught that the image made on the retina is conveyed along the optic nerve to the brain. Razi was the first to recognize the reaction of the pupil to light and Ibn Sina was the first to describe the exact number of extrinsic muscles of the eyeball, namely six. The greatest contribution of Islamic medicine in practical ophthalmology was in the matter of cataract. The most significant development in the extraction of cataract was developed by Ammar bin Ali of Mosul, who introduced a hollow metallic needle through the sclerotic and extracted the lens by suction. Europe rediscovered this in the nineteenth century.

PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacology took roots in Islam during the 9th century. Yuhanna bin Masawayh (777-857 A.D.) started scientific and systematic applications of therapeutics at the Abbasids capital. His students Hunayn bin Ishaq al-lbadi (809-874 A.D.) and his associates established solid foundations of Arabic medicine and therapeutics in the ninth century. In his book al-Masail Hunayn outlined methods for confirming the pharmacological effectiveness of drugs by experimenting with them on humans. He also explained the importance of prognosis and diagnosis of diseases for better and more effective treatment.

Pharmacy became an independent and separate profession from medicine and alchemy. With the wild sprouting of apothecary shops, regulations became necessary and imposed to maintain quality control.” The Arabian apothecary shops were regularly inspected by a syndic (Muhtasib) who threatened the merchants with humiliating corporal punishments if they adulterated drugs.” As early as the days of al-Mamun and al-Mutasim pharmacists had to pass examinations to become licensed professionals and were pledged to follow the physician’s prescriptions. Also by this decree, restrictive measures were legally placed upon doctors, preventing them from owning or holding stock in a pharmacy.

Methods of extracting and preparing medicines were brought to a high art, and their techniques of distillation, crystallization, solution, sublimation, reduction and calcinations became the essential processes of pharmacy and chemistry. With the help of these techniques, the Saydalanis (pharmacists) introduced new drugs such as camphor, senna, sandalwood, rhubarb, musk, myrrh, cassia, tamarind, nutmeg, alum, aloes, cloves, coconut, nuxvomica, cubebs, aconite, ambergris and mercury. The important role of the Muslims in developing modern pharmacy and chemistry is memorialized in the significant number of current pharmaceutical and chemical terms derived from Arabic: drug, alkali, alcohol, aldehydes, alembic, and elixir among others, not to mention syrups and juleps. They invented flavorings extracts made of rose water, orange blossom water, orange and lemon peel, tragacanth and other attractive ingredients. Space does not permit me to list the contributions to pharmacology and therapeutics, made by Razi, Zahrawi, Biruni, Ibn Butlan, and Tamimi.

PYCHOTHERAPY

From freckle lotion to psychotherapy- such was the range of treatment practiced by the physicians of Islam. Though freckles continue to sprinkle the skin of 20th century man, in the realm of psychosomatic disorders both al-Razi and Ibn Sina achieved dramatic results, antedating Freud and Jung by a thousand years. When Razi was appointed physician-in-chief to the Baghdad Hospital, he made it the, first hospital to have a ward exclusively devoted to the mentally ill.”

Razi combined psychological methods and physiological explanations, and he used psychotherapy in a dynamic fashion, Razi was once called in to treat a famous caliph who had severe arthritis. He advised a hot bath, and while the caliph was bathing, Razi threatened him with a knife, proclaiming he was going to kill him. This deliberate provocation increased the natural caloric which thus gained sufficient strength to dissolve the already softened humours; as a result the caliph got up from is knees in the bath and ran after Razi. One woman who suffered from such severe cramps in her joints that she was unable to rise was cured by a physician who lifted her skirt, thus putting her to shame. “A flush of heat was produced within her which dissolved the rheumatic humour.”

The Arabs brought a refreshing spirit of dispassionate clarity into psychiatry. They were free from the demonological theories which swept over the Christian world and were, therefore, able to make clear cut clinical observations on the mentally ill.

Najab ud din Muhammad, a contemporary of Razi, left many excellent descriptions of various mental diseases. His carefully compiled observation on actual patients made up the most complete classification of mental diseases theretofore known.” Najab described agitated depression, obsessional types of neurosis, Nafkhae Malikholia (combined priapism and sexual impotence). Kutrib (a form of persecutory psychosis), Dual-Kulb (a form of mania).

Ibn Sina recognized ‘physiological psychology’ in treating illnesses involving emotions. From the clinical perspective, Ibn Sina developed a system for associating changes in the pulse rate with inner feelings which have been viewed as anticipating the word association test of Jung. He is said to have treated a terribly ill patient by feeling the patient’s pulse and reciting aloud to him the names of provinces, districts, towns, streets, and people. By noticing how the patient’s pulse quickened when names were mentioned Ibn Sina deduced that the patient was in love with a girl whose home Ibn Sina was able to locate by the digital examination. The man took Ibn Sina‘s advice, married the girl, and recovered from his illness.

It is not surprising to know that at Fez, Morocco, an asylum for the mentally ill had been built early in the 8th century, and insane, asylums were built by the Arabs also in Baghdad in 705 A.D., in Cairo in 800 A.D., and in Damascus and Aleppo in 1270 A.D. In addition to baths, drugs, kind and benevolent treatment given to the mentally ill, music therapy and occupational therapy were also employed. These therapies were highly developed. Special choirs and live music bands were brought daily to entertain the patients by providing singing and musical performances and comic performers as well.

CONCLUSION

1,000 years ago Islamic medicine was the most advanced in the world at that time. Even after ten centuries, the achievements of Islamic medicine look amazingly modern. 1,000 years ago the Muslims were the great torchbearers of international scientific research. Every student and professional from each country outside the Islamic Empire, aspired, yearned, a dreamed to go to the Islamic universities to learn, to work, to live and to lead a comfortable life in an affluent and most advanced and civilized society. Today, in this twentieth century, the United States of America has achieved such a position. The pendulum can swing back. Fortunately, Allah has given a bounty to many Islamic countries – an income over 100 billion dollars per year. Hence Islamic countries have the opportunity and resources to make Islamic science and medicine number one in the world, once again.

REFERENCES

1. M.H. Hart “The 100: A Rankin of the Most Influential Persons in History.”, Hart Publishing Co., New York, 1978.

2. S.H.Nasr, “Science and Civilization in Islam.” New American Library, Inc., New York, 1968, pp. 184-229.

3 .A. Salam, IAEA Bulletin, 22(2), 81-83, (1980).

4. D.Campbell, “Arabian Medicine”, Vol. 1, Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. LTD., London, 1926.

5. E.G.Browne,”Arabian Medicine”,Cambridge University M.Sirajud- din and Sons, Publishers, Lahore, 1962, pp. 5-16.

6. G. Podgomy, N. Carolina Med. J. 27, 197-208, (1966).

7. A.S. Lyons, and R.J. Petruccelli, “Medicine – An Illustrated History”, H.N. Abrams Inc., Publishers, New York, 1978, pp. 295-317.

8. F.H. Garrison, “History of Medicine”. 4th edition, W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1929, p. 134.

9. G. Elgood. “A Medical History of Persia”, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 195 1, pp. 278-301.

10. H.N. Wasty, “Muslim Contribution to Medicine”, M. Sirajuddin and Sons, Publishers, Lahore, 1962, pp. 5-16.

11. S. Hamarneh, Sudhoffs Archiv fur Geschichte der medizin und der Naturwissenschaften, 48, 159-173.

12. E. Abouleish, J. Islamic Med. Asso., lo(3, 4), 28-45, (1979).

13. F.S. Haddad, Leb. Med. J. 26, 331-346, 1979).

14. Y.A. Shahine, “The Arab Contribution to Medicine”, Longman for the University of Essex, London, 1971, p. 10.

15. B. Miller, Mankind, 6(8), 8-40, (1980).

16. “Aspects of Muslim Civilization”. Pakistan Branch of Oxford University Press, Lahore, 1961, pp. 53.

17. T.E. Keys, K.G. Wakim, Mayo Clinic Proceedings of the Staff Meeting, 28, 423-437, (1953).

18. M. Siddiqi, “Studies in Arabic and Persian Medical Literature”, Calcutta University, Calcutta, 1959, p. XX.

19. L. Burton, “1001 Nights (Six Volumes)”, 1886.

20. P. Hitti, “The Arabs: A Short History”, Henry Regnery, Chicago, 1943,P.143.

21. A Castiglioni, “A History of Medicine”, E. Krumbhaar (trans.), Alfred A.Knopf, New York, 1958, p. 268.

22. C. Singer and A.A. Underwood, “A Short History of Medicine”, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, 1962, p. 76.

23. A.A. Khairallah, Ann. Med. Hist. 34, 409-415

24. Al-Oakbi, Hospital Med. Prac., Cairo, 1, 14-29, (1971).

25. F. S. Haddad, “XXI International Congress of the History of Medicine” (Sienna 1968, Sep. 22) 1970, pp. 1600 -1607.

26. G.A. Bender, “Great Moments in Medicine”. Parke-Davis, Detroit, 1961, p. 68-74.

27. G. Fisher, Ann. Anat, Surg., 6, 217-217, (1882).

28. E.D. Whitehead and R.B. Bush, Invest, Urology, 5

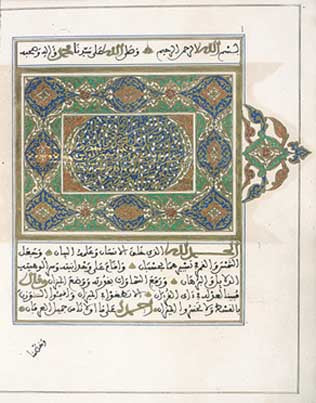

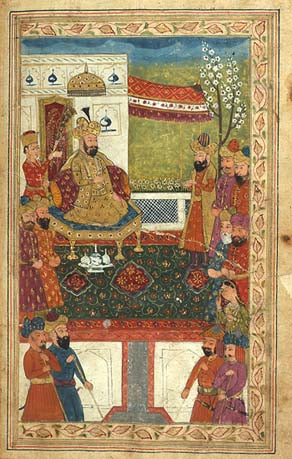

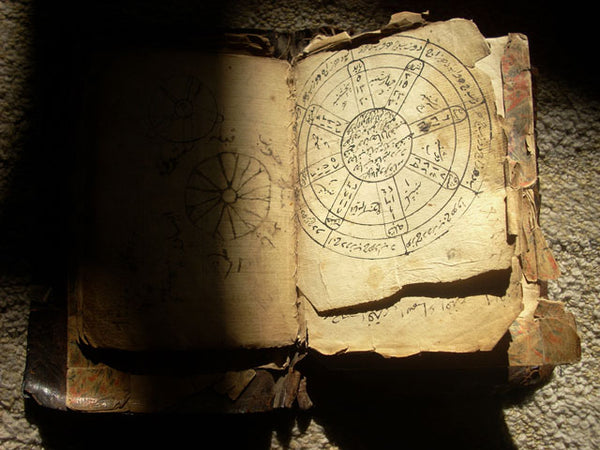

The image used in this article is taken from Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine, go to:

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/catalog_tb.html

Leave a comment

Also in SCIENCE & MEDICINE

Revolution by the Ream

Paper, one of the most ubiquitous materials in modern life, was invented in China more than 2000 years ago. Nearly a millennium passed, however, before Europeans first used it, and they only began to manufacture it in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Muslims had established the first paper mills in Spain. The German Ulman Stromer, who had seen paper mills in Italy, built the first one north of the Alps at Nuremberg in the late 14th century.

The cultural revolution begun by Johann Gutenberg's printing press in 15th-century Mainz could not have taken place without paper mills like Stromer's, for even the earliest printing presses produced books at many times the speed of hand copyists, and had to be fed with reams and reams of paper. Our demand for paper has never been satisfied since, for we constantly develop new uses for this versatile material and new sources for the fiber from which it is made. Even today, despite the computer's promise to provide us with "paperless offices," we all use more paper than ever before, not only for communication but also for wrapping, filtering, construction and hundreds of other purposes.

Scientific Inventions by Muslims

Inventions

Abul Hasan is distinguished as the inventor of the Telescope, which he described to be a Tube, to the extremities of which were attached diopters”.

The Great Explorers of Islam

It was an Arab caravan which brought Hazrat Yusuf (Prophet Joseph) to Egypt. Moreover, the fertile areas in Arabia including Yemen, Yamama, Oman, Bahrein and Hadari-Maut were situated on the coast, and the Arabs being sea-faring people took sea routes in order to reach these places and fulfilling their commercial ventures.