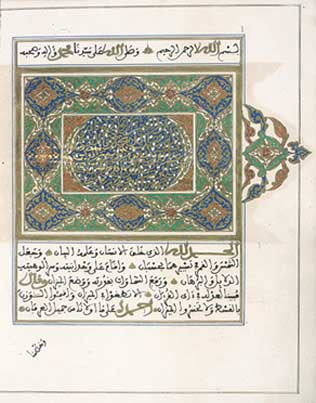

Revolution by the Ream

Paper, one of the most ubiquitous materials in modern life, was invented in China more than 2000 years ago. Nearly a millennium passed, however, before Europeans first used it, and they only began to manufacture it in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Muslims had established the first paper mills in Spain. The German Ulman Stromer, who had seen paper mills in Italy, built the first one north of the Alps at Nuremberg in the late 14th century.

The cultural revolution begun by Johann Gutenberg's printing press in 15th-century Mainz could not have taken place without paper mills like Stromer's, for even the earliest printing presses produced books at many times the speed of hand copyists, and had to be fed with reams and reams of paper. Our demand for paper has never been satisfied since, for we constantly develop new uses for this versatile material and new sources for the fiber from which it is made. Even today, despite the computer's promise to provide us with "paperless offices," we all use more paper than ever before, not only for communication but also for wrapping, filtering, construction and hundreds of other purposes.

Scientific Inventions by Muslims

Inventions

Abul Hasan is distinguished as the inventor of the Telescope, which he described to be a Tube, to the extremities of which were attached diopters”.

The Great Explorers of Islam

It was an Arab caravan which brought Hazrat Yusuf (Prophet Joseph) to Egypt. Moreover, the fertile areas in Arabia including Yemen, Yamama, Oman, Bahrein and Hadari-Maut were situated on the coast, and the Arabs being sea-faring people took sea routes in order to reach these places and fulfilling their commercial ventures.

Muslim Contributions to the Sciences

Doctor, Philosopher, Renaissance Man

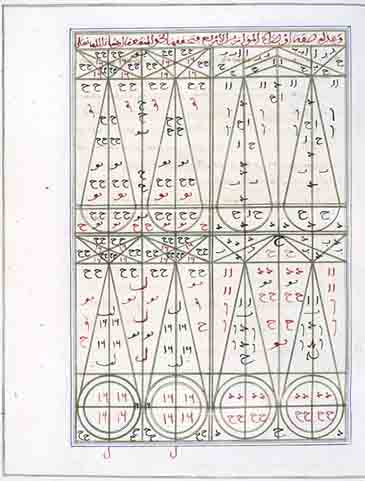

The Great Mathematicians of Islam

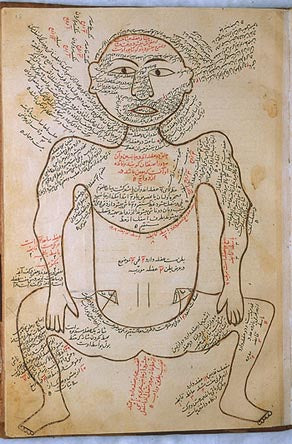

Contributions of Muslims to the Field of Medicine

In the field of medical knowledge, Muslim scientists had several sources on which to base their studies. The first source was Islamic teachings, including many religious requirements concerning hygiene. In addition, there is a saying attributed to Prophet Muhammad that for every disease, God has created a cure. The second source of learning was the body of Greek medical knowledge, developed by Hippocrates and Galen. These contributions were easily integrated into the study of Muslim medicine due to their focus on harmony and balance. A third source was the traditions practiced by Persians, Indians and others who practiced medicine at the teaching center of Jundi-Shapur (Iran). Both Jundi-Shapur and Baghdad had well-developed teaching Hospitals which attracted physicians from afar to study under famous teachers. Among the physicians who helped found the teaching hospital at Baghdad was the Bakhtishu family of doctors, non-Muslims who worked under the patronage of the Muslim rulers.

Islamic Medicine: 1,000 Years Ahead of It's Time

Within a century after the death of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) the Muslims not only conquered new lands but also became scientific innovators with originality and productivity. They hit the source ball of knowledge over the fence to Europe. By the ninth century, Islamic medical practice had advanced from talisman and theology to hospitals with wards, doctors who had to pass tests, and the use of technical terminology. The then Baghdad General Hospital incorporated innovations which sound amazingly modern. The fountains cooled the air near the wards of those afflicted with fever; the insane were treated with gentleness, and at night the pain of the restless was soothed by soft music and storytelling. The prince and pauper received identical attention; the destitute upon discharge received five gold pieces to sustain them during convalescence. While Paris and London were places of mud streets and hovels, Baghdad, Cairo, and Cardboard had hospitals open to both male and female patients; staffed by attendants of both sexes. These medical centers contained libraries pharmacies, the system of interns, externs, and nurses. There were mobile clinics to reach the totally disabled, the disadvantaged and those in remote areas. There were regulations to maintain quality control on drugs. Pharmacists became licensed professionals and were pledged to follow the physician’s prescriptions. Legal measures were taken to prevent doctors from owning or holding stock. in a pharmacy. The extent to which Islamic medicine advanced in the fields of medical education, hospitals, bacteriology, medicine, anaesthesia, surgery, pharmacy, ophthalmology, psychotherapy, and psychosomatic diseases are presented briefly.

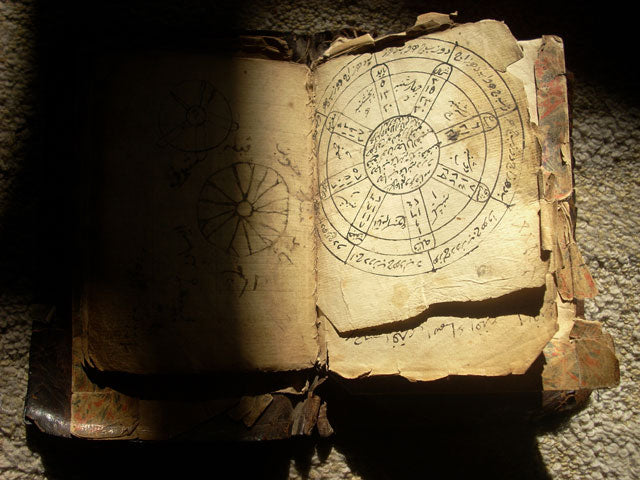

Facts on Astronomy From the Qur’an

Allah said: This is no less than a reminder to (all) the worlds. And you shall certainly know the truth of it (all) after a while. (Qur’an 38:87-88).

Thus, the Qur’an is a reminder for all of mankind until the Last Hour. It contains information that man discovers in due time. Because this Qur’an was revealed from Allahs knowledge and every single verse in it was revealed with Allahs knowledge, as He Himself said:

But Allah bears witness that what He has sent unto you He has sent with His (own) knowledge… (Qur’an 4:166).

Fact File on Muslim Contributions to Science and Technology

No discipline is void of their names: medicine and surgery, pharmacy and pharmacology, engineering and technology, astronomy and astrology, mathematics and physics, chemistry and geography, botany and zoology, philosophy and history, arts and culture. It is only the ignominy that has become a part of our “rich” tradition of forgetting our transition from Greek to Western supremacy.

Health Guidelines From Qur'an and Sunnah

The Quran is not a book of medicine or of health sciences,but in it there are hints which lead to guidelines in health and diseases. Prophet Mohammed (P.B.U.H.) has set as an example to the mankind so his traditions in matters of health and personal hygienic are also a guide for his followers.

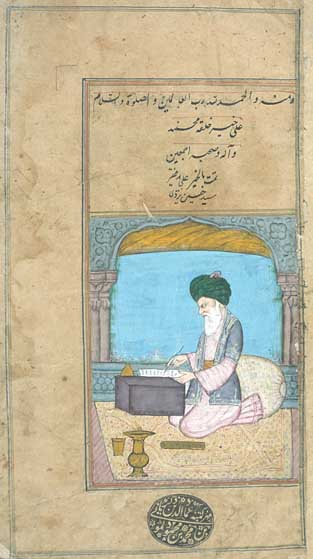

Revolution by the Ream

Paper, one of the most ubiquitous materials in modern life, was invented in China more than 2000 years ago. Nearly a millennium passed, however, before Europeans first used it, and they only began to manufacture it in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Muslims had established the first paper mills in Spain. The German Ulman Stromer, who had seen paper mills in Italy, built the first one north of the Alps at Nuremberg in the late 14th century.

The cultural revolution begun by Johann Gutenberg's printing press in 15th-century Mainz could not have taken place without paper mills like Stromer's, for even the earliest printing presses produced books at many times the speed of hand copyists, and had to be fed with reams and reams of paper. Our demand for paper has never been satisfied since, for we constantly develop new uses for this versatile material and new sources for the fiber from which it is made. Even today, despite the computer's promise to provide us with "paperless offices," we all use more paper than ever before, not only for communication, but also for wrapping, filtering, construction and hundreds of other purposes.

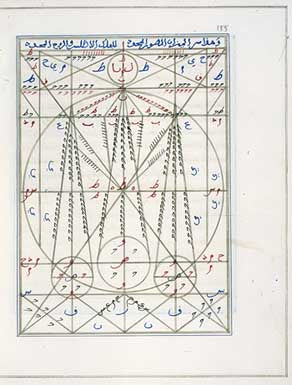

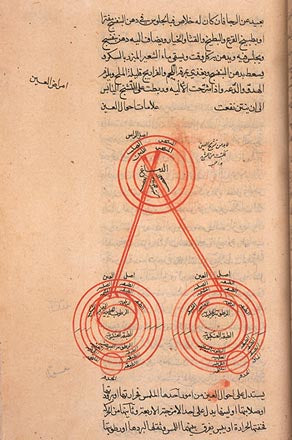

The Muslim Contribution to Optics

Karima Burns is a naturopath and herbalist. She has published her own newsletter about natural healing for five years and has studied many aspects of natural healing such as herbs, nutrition, homoeopathy and aromatherapy for the past 13 years.

There is still a controversy as to whether colour therapy works within the realm of vibration or within the world of the brain. And Muslims would be pleased to know that this debate would not even be possible without the Muslim contribution to optics and to the discovery of how colours work.

Before Muslim scientists took over the field of optics, Euclidic and Platonic thinkers believed that the eye was the source of light, and that the world would actually be dark if not for the illumination that the eye provided. It was thought that the mixture of this darkness with light produced colours.

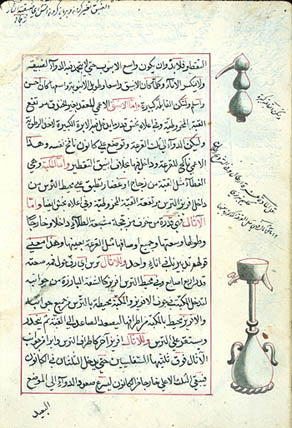

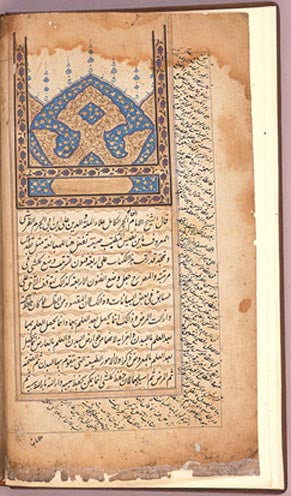

Prophetic Medicine: Between the Nass and Empirical Experience

Tibb Nabawi refers to words and actions of the Prophet with a bearing on disease, treatment of disease, and care of patients. Thus also included are words of the prophet on medical matters, medical treatment practiced by others on the prophet, medical treatments practised by the prophet on himself and others, medical treatments observed by the prophet with no objections, medical procedures that the prophet heard or knew about and did not prohibit, or medical practices that were so common that the prophet could not have failed to know about them. The prophet’s medical teachings were specific for place, population, and time. They however also included general guidance on physical and mental health that are applicable to all places, all times, and all circumstances. Tibb nabawi is not one monolithic or systematic medical system as some people would want us to believe. It is varied and circumstantial. It covers preventive medicine, curative medicine, mental well-being, spiritual cures or ruqyah, medical and surgical treatments. It integrates mind & body, matter and spirit.

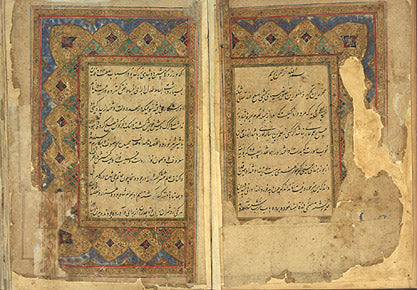

The Arab Roots of European Medicine

In the "General Prologue" of The Canterbury Tales , Geoffrey Chaucer identifies the authorities used by his "Doctour of Physic" in the six lines quoted above. The list includes four Arab physicians: Jesu Haly (Ibn 'Isa), Razi (Al-Razi, or Rhazes), Avycen (Ibn Sina, or Avicenna) and Averrois (Ibn Rushd, or Averroes). These four did not make Chaucer's list only to add an exotic flavor to his late-14th-century poetry. Chaucer cited them because they were regarded as among the great medical authorities of the ancient world and the European Middle Ages, physicians whose textbooks were used in European medical schools, and would be for centuries to come. First collecting, then translating, then augmenting and finally codifying the classical Greco-Roman heritage that Europe had lost, Arab physicians of the eighth to eleventh century laid the foundations of the institutions and the science of modern medicine.

Columbus – What if?

Arabic had been the scientific language of most of humankind from the eighth to the 12th century. It is probably for this reason that Columbus, in his own words, considered Arabic to be “the mother of all languages,” and why, on his first voyage to the New World, he took with him Luis de Torres, an Arabic-speaking Spaniard, as his interpreter.

Columbus fully expected to land in India, where he knew that the Arabs had preceded him. He also knew that, for the past five centuries, Arabs had explored, and written of, the far reaches of the known world. They had been around the perimeter of Africa and sailed as far as India. They had ventured overland beyond Constantinople, past Asia Minor, across Egypt and Syria – then the western marches of the unknown Orient – and into the heart of the Asian continent. They had mapped the terrain, traced the course of rivers, timed the monsoons, scaled mountains, charted shoals and reached China, and, as a result, had spread Islam and the Arabic language in all these regions (See Aramco World, November-December 1991).

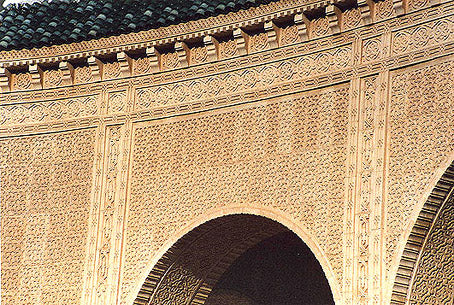

Science in Al-Andalus

As far as the West was concerned, the Arab invasion did unlock an enchanted palace. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, Vandals, Huns and Visigoths had pillaged and burned their way through the Iberian Peninsula, establishing ephemeral kingdoms which lasted only as long as loot poured in, and were then destroyed in their turn. Then, without warning, in the year 711, came the Arabs - to settle, fall in love with the land and create the first civilization Europe had known since the Roman legions had given up the unequal fight against the barbarian hordes.

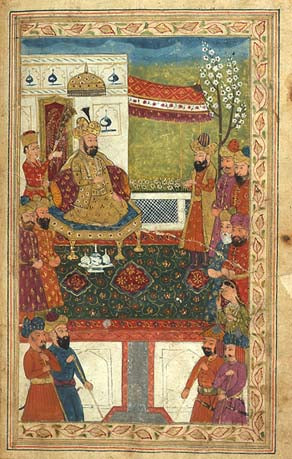

Spain first prospered under the rule of the Umayyads, who established a dynasty there after they had lost the caliphate in the east to the Abbasids. At first, the culture of the Umayyad court at Cordoba was wholly derivative. Fashions, both in literature and dress, were imitative of those current in the Abbasids' newly founded capital of Baghdad. Scholars from the more sophisticated lands to the east were always assured of a warm reception at the court of Cordoba, where their colleagues would listen avidly for news of what was being discussed in the capital, what people were wearing, what songs were being sung, and - above all - what books were being read.

Science – The Islamic Legacy

The Arabs were the inheritors of the scientific tradition of late antiquity. They preserved it, elaborated it, and, finally, passed it on to Europe.

The story of how this came about is far from simple, and much research needs to be done before its details are completely understood, but the broad outlines are clear.

When Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Asia Minor and Persia fell to Islamic forces in the seventh century they included a heterogeneous population. Although the cultivated classes of the former provinces of the Byzantine Empire spoke Greek, the people spoke a number of other languages -Coptic in Egypt and various Aramaic dialects in Syria and Iraq. These populations were for the most part Christian. In Persia, the majority language was Pahlavi an earlier form of the language spoken there today - and the state religion was Zoroastrianism, with substantial Christian minorities and a few centers of Buddhism.