Muslim Contributions to the Sciences

The Islamic Scholar CD ROM, Saturday 27 September 2003

The Arabs who had wielded the arms with such remarkable success, that they had become the masters of a third of the known world in a short span of thirty years, met with even greater success in the realm of knowledge. But the West has persistently endeavoured to under-rate the achievements of Islam. Writing in his outspoken book The intellectual Development of Europe, John William Draper says, “I have to deplore the systematic manner in which the literature of Europe has contrived to put out of sight our scientific obligations to the Mohammadans. Surely they can not be much longer hidden. Injustice founded on religious rancour and national conceit cannot be perpetuated forever. What should the modern astronomer say, when, remembering the contemporary barbarism of Europe, he finds the Arab Abul Hassan speaking of turbes, to the extremities of which ocular and object diopters, perhaps sights, were attached, as used at Meragha? What when he reads of the attempts of Abdur Rahman Sufi at improving the photometry of stars? Are the astronomical tables of Ibn Junis (A.D. 1008) called the Hakemite tables, or the Ilkanic tables of Nasir-ud-din Toosi, constructed at the great observatory just mentioned, Meragha near Tauris (1259 A.D.), or the measurement of time by pendulum oscillations, and the method of correcting astronomical tables by systematic observations are such things worthless indications of the mental State? The Arab has left his intellectual impress on Europe, as, before long, Christendom will have to confess; he has indelibly written it on the heavens, as anyone may see who reads the names of the stars on a common celestial globe.”

What is Science?

Science has been defined as, “the ordered knowledge of natural phenomena and the relations between them. Its end is the rational interpretation of the facts of existence as disclosed to us by our faculties and senses.” The celebrated scientist Sir J. Arthur Thomson considers science to be “the well-criticised body of empirical knowledge declaring in the simplest and tersest terms available at the time what can be observed and experimented with, and summing up uniformities of change in formulae which are called laws verifiable by all who can use the methods.” According to another well-known scientist Karl Pearson the hypotheses of science are based on “observed facts, which, when confirmed by criticism and experiment, are turned into laws of Nature.”

Experimental Method

Observation and experiment are the two sources of scientific knowledge. Aristotle was the father of the Greek sciences and has made a lasting contribution to physics, astronomy, biology, meteorology and other sciences. The Greek method of acquiring scientific knowledge was mainly speculative; hence science as such could make little headway during the time of the Greeks.

The Arabs who were more realistic and practical in their approach adopted the experimental method to harness scientific knowledge. Observation and experiment formed the vehicle of their scientific pursuits; hence they gave a new outlook to the science of which the world had been totally unaware. Their achievements in the field of experimental science added a golden chapter to the annals of scientific knowledge and opened a new vista for the growth of modern sciences. Al-Ghazali was the follower of Aristotle in logic, but among Muslims, Ishraqi and Ibn-iTaimiyya were first to undertake the systematic refutation of Greek logic. Abu Bakr Razi criticised Aristotle’s first figure and followed the inductive spirit which was reformulated by John Stuart Mill. Ibn-i-Hazm in his well known work Scope of Logic lays stress on sense perception as a source of knowledge and Ibn-i-Taimiyya in his Refuttion of Logic proves beyond doubt that induction is the only sure form of argument, which ultimately gave birth to the method of observation and experiment. It is absolutely wrong to assume that experimental method was formulated in Europe. Roger Bacon, who, in the west is known as the originator of experimental method in Europe, had himself received his training from the pupils of Spanish Moors, and had learnt everything from Muslim sources. The influence of Ibn Haitham on Roger Bacon is clearly visible in his works. Europe was very slow to recognise the Islamic origin of her much advertised scientific (experimental) method.

Writing in the Making of Humanity Briffault admits, “It was under their successors at the Oxford School that Roger Bacon learned Arabic and Arabic science. Neither Roger Bacon nor his later namesake has any title to be credited with having introduced the experimental method. Roger Bacon was no more than one of the apostles of Muslim science and method to Christian Europe; and he never wearied of declaring that the knowledge of Arabic and Arabic science was for his contemporaries the only way to true knowledge. Discussions as to who was the originator of the experimental method……are part of the colossal misrepresentation of the origins of European civilization. The experimental method of Arabs was by Bacon’s time widespread and eagerly cultivated throughout Europe….Science is the most momentous contribution of Arab civilization to the modern world, but its fruits were slow in ripening. Not until long after Moorish culture had sunk back into darkness did the giant to which it had given birth, rise in his might. It was not science only which brought Europe back to life. Other and manifold influences from the civilisation of Islam communicated its first glow to European life. For although there is not a single aspect of European growth in which the decisive influence of Islamic culture is not traceable, nowhere is it so clear and momentous as in the genesis of that power which constitutes the permanent distinctive force of the modern world, and the supreme source of its victory-natural science and the scientific spirit.., The debt of our science to that of the Arabs does not consist in startling discoveries or revolutionary theories; science owes a great deal more to Arab culture, it owes its existence….The ancient world was, as we saw, pre-scientific. The astronomy and mathematics of Greeks were a foreign importation never thoroughly acclimatized in Greek culture. The Greeks systematised, generalised and theorised, but the patient ways of investigations, the accumulation of positive knowledge, the minute methods of science, detailed and prolonged observation and experimental enquiry were altogether alien to the Greek temperament. Only in Hellenistic Alexandria was any approach to scientific work conducted in the ancient classical world. That spirit and those methods were introduced into the European world by the Arabs.”‘

In his outstanding work The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, Dr. M. Iqbal, the poet of Islam writes, “The first important point to note about the spirit of Muslim culture then is that for purposes of knowledge, it fixes its gaze on the concrete, the finite. It is further clear that the birth of the method of observation and experiment in Islam was due not to a compromise with Greek thought but to prolonged intellectual warfare with it. In fact the influence of Greeks who, as Briffault says, were interested chiefly in theory, not in fact, tended rather to obscure the Muslim’s vision of the Quran, and for at least two centuries kept the practical Arab temperament from asserting itself and coming to its own.” Thus the experimental method introduced by the Arabs was responsible for the rapid advancement of science during the mediaeval times.

Chemistry

Chemistry as a science is unquestionably the invention of the Muslims. It is one of the sciences in which Muslims have made the greatest contribution and developed it to such a high degree of perfection that they were considered authorities in this science until the end of the 17th century A. D. Jabir and Zakariya Razi have the distinction of being the greatest chemists the mediaeval times produced. Writing in his illuminating History of the Arabs, Philip K. Hitti acknowledges the greatness of Arabs in this branch of science when he says, “After materia medica, astronomy and mathematics, the Arabs made their greatest scientific contribution in chemistry. In the study of chemistry and other physical sciences, the Arabs introduced the objective experiment, a decided improvement over the hazy speculation of Greeks. Accurate in the observation of phenomena and diligent in the accumulation of facts, the Arabs nevertheless found it difficult to project proper hypotheses.”

Jabir Ibn Hayyan (Geber) who flourished in Kufa about 776 A.D. is known as the father of modern chemistry and along with Zakariya Razi, stands as the greatest name in the annals of chemical science during mediaeval times. He got his education from Omayyad Prince Khalid Ibn Yazid Ibn Muawiyah and the celebrated Imam Jafar al-Sadiq . He worked on the assumption that metals like lead, tin and iron could be transformed into gold by mixing certain chemical substances. It is said that he manufactured a large quantity of gold with the help of that mysterious substance and two centuries later, when a street was rebuilt in Kufa a large piece of gold was unearthed from his laboratory. He laid great emphasis on the importance of experimentation in his research and hence he made great headway in chemical science, Western writers credit him with the discovery of several chemical compounds, which are not mentioned in his twenty-two extant Arabic works.

According to Max Meyerh of “His influence may be traced throughout the whole historic course of European alchemy and chemistry.” He is credited, with the writing of 100 chemical works. “Nevertheless, the works to which his name was attached” says Hitti, “were after the 14th century, the most influential chemical treatises in both Europe and Asia.”” He explained scientifically the two principal operations of chemistry, calcination and reduction, and registered a marked improvement in the methods of evaporation, sublimation filtration, distillation and crystallization. Jabir modified and corrected the Aristotelian theory of the constituents of metal, which remained unchanged until the beginning of modern chemistry in the 18th century. He has explained in his works the preparation of many chemical substances including “Cinnabar” (sulphide of mercury) and arsenic oxide. It has been established through historical research that he knew how to obtain nearly pure vitrilos, alums, alkalis and how to produce ‘the so-called liver’ and milk of sulphur by heating sulphur with alkali. He prepared mercury oxide and was fully conversant with the preparation of crude sulphuric and nitric acids. He knew the method of the solution of gold and silver with this acid. His chemical treatises on such subjects have been translated into several European languages including Latin and several technical scientific terms invented by Jabir have been adopted in modern chemistry. A real estimate of his achievements is only possible when his enormous chemical work including the Book of Seventy are published. Richard Russell (1678, A.D.) an English translator ascribes a book entitled Sun of Perfection to Jabir. A number of his chemical works have been published by Berthelot. His books translated into English are the Book of Kingdom, Book of Balances and Book of Eastern mercury. Jabir also advanced a theory on the geologic formation of metals and dealt with many useful practical applications of chemistry such as refinement of metals, preparation of steel and dyeing of cloth and leather, varnishing of waterproof cloth and use of manganese dioxide to colour glass.

Jabir was recognised as the master by the later chemists including al-Tughrai and Abu al-Qasim al-Iraqi who flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries respectively. These Muslim chemists made little improvement on the methods of Jabir. They confined themselves to the quest of the legendary elixir which they could never find.

Zakariya Razi known as Rhazas in Latin is the second great name in mediaeval chemical science. Born in 850 A.D. at Rayy, he is known as one of the greatest physicians of all times. He wrote Kitab al Asrar in chemistry dealing with the preparation of chemical substances and their application. His great work of the art of alchemy was recently found in the library of an Indian prince. Razi has proved himself to be a greater expert than all his predecessors, including Jabir, in the exact classification of substances. His description of chemical experiments as well as their apparatus are distinguished for their clarity which were not visible in the writings of his predecessors. Jabir and other Arabian chemists divided mineral substances into bodies (gold, silver etc.), souls (sulphur, arsenic, etc.) and spirits (mercury and sal-ammoniac) while Razi classified his mineral substances as vegetable, animal and mineral.

The mineral substances were also classified by Al-Jabiz. Abu Mansur Muwaffaq has contributed to the method of the preparation and properties of mineral substances. Abul Qasim who was a renowned chemist prepared drugs by sublimation and distillation. High-class sugar and glass were manufactured in Islamic countries. The Arabs were also expert in the manufacture of ink, lacquers, solders, cement and imitation pearls.

Physics

The Holy Quran had awakened a spirit of enquiry among the Arabs which was instrumental in their splendid achievements in the field of science, and according to a western critic led them to realise that “science could not be advanced by mere speculation; its only sure progress lay in the practical interrogation of nature. The essential characteristics of their method are experiment and observation. In their writings on Mechanics, hydrostatics, optics, etc., the solution of the problem is always obtained by performing an experiment, or by an instrumental observation. It was this that made them the originator of chemistry, that led them to the invention of all kinds of apparatus for distillation, sublimation, fusion and filtration; that in astronomy caused them to appeal to divided instrument, as quadrant and astrolabe; in chemistry to employ the balance the theory of which they were perfectly familiar with; to construct tables of specific gravities and astronomical tables, that produced their great improvements in geometry and trigonometry.”

The Muslims developed physics to a high degree and produced such eminent physicist as Kindi, Jahiz, Banu Musa, Beruni, Razi and Abdur Rahman Ibn Nasr.

Abu Yusuf Ibn Ishaq, known as al-Kindi was born at Kufa in the middle of the 9th century and flourished in Baghdad. He is the most dominating and one of the greatest Muslim scholars of physics. Over and above this, he was an astrologer, philosopher, alchemist, optician and musical theorist. He wrote more than 265 books, the majority of which have been lost. Most of his works which survived are in Latin having been translated by Gerard of Cremona. Of these fifteen are on meteorology, several on specific weight, on tides, on optics and on reflection of light, and eight are on music. His optics influenced Roger Bacon. He wrote several books on iron and steel to be used for weapons. He applied mathematics not only to physics but also to medicine. He was therefore regarded by Cardon, a philosopher of the Renaissance, “as one of the 12 subtlest minds.” “He thought that gold and silver could only be obtained from mines and not through any other process. He endeavoured to ascertain the laws that govern the fall of bodies. Razi investigated on the determination of specific gravity of means of hydrostatic balance, called by him Mizan-al-Tabii. Most of his works on physics, mathematics, astronomy and optics have perished. In physics, his writings deal with matter, space, time and motion. In his opinion matter in the primitive state before the creation of the world was composed of scattered atoms, which possessed extent. Mixed in various proportions with the articles of void, these atoms produced these elements which are five in number namely earth, air, water, fire and celestial element. Fire is created by striking iron on the stone.

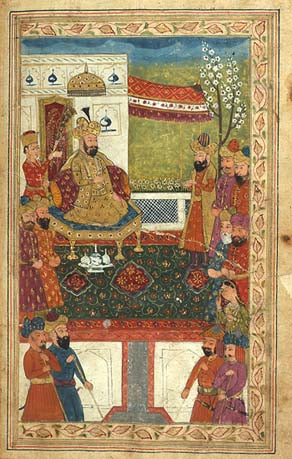

Abu Rehan Beruni, was a versatile genius, who adorned the durbar of Mahmud of Ghazni. His outstanding achievement in the realm of physics was the accurate determination of the weight of 18 stones. He also discovered that light travels faster than sound. He has also contributed immensely to geological knowledge by providing the correct explanation of the formation of natural spring and artesian wells. He suggested that the Indus valley was formerly an ancient basin filled with alluvial soil. His Kitab al Jawahir deals with different types of gems and their specific gravity. A voluminous unedited lapidary by Betuni is kept in manuscript form in the Escorial Library. It deals with a large number of stones and metals from the natural, commercial and medical point of view. Barlu Musa has left behind him a work on balance, while Al-Jahiz used hydrostatic balance to determine specific gravity. An excellent treatise had been written by Al-Naziri regarding atmosphere.

Khazini, was a well-known scientist of Islam, who explained the greater density of water when nearer to the centre of the earth. Roger Bacon, who proved the same hypotheses afterwards, based his proof on the theories advanced by Khazini. His brilliant work Mizanul Hikma deals with gravity and contains tables of densities of many solids and liquids. It also contains “observation on capillarity uses of aerometer to measure densities and appreciate the temperature of liquids, theory of the lever and the application of balance to building.” Chapters on weights and measures’ were written by Ibn Jami and Al-Attar. Abdur Rahman Ibn Nasr wrote an excellent treatise on weights and measures for the use of Egyptian markets.

Biology

The Muslim scientists made considerable progress in biology especially in botany, and developed horticulture to a high degree of perfection. They paid greater attention to botany in comparison to zoology. Botany reached its zenith in Spain. In zoology the study of the horse was developed almost to the tank of a science. Abu Ubaidah (728–825 A. D.) who wrote more than 100 books, devoted more than fifty books to the study of the horse.

Al-Jahiz, who flourished in Basra is reputed to be one of the greatest zoologists the Muslim world has produced. His influence in the subject may be traced to ‘the Persian ‘Al-Qazwini’ and the Egyptian ‘Al-Damiri’. His book ‘Ritab al Haywan’ (book on animals) contains germs of later theories of evolution, adaptation and animal psychology. He was the first to note changes in bird life through migrations; Re-described the method of obtaining ‘ammonia from animal offal by dry distilling.’

Al-Damiri, who died in 1405 in Cairo and who was influenced by Al-Jahiz is the greatest Arab zoologist. His book Hayat Haywarz (Life of animal) is the most important Muslim work in zoology. It is an encyclopaedia on animal life containing a mine of information on the subject. It contains the history of animals and preceded Buffon by 700 years.

Al-Masudi, has given the rudiments of the theory of evolution in his well known work Meadows of gold. Another of his works Kitab al-Tanbih wal Ishraq advances his views on evolution namely from mineral to plant, from plant to animal and from animal to man.

In botany Spanish Muslims made the greatest contribution, and some of them are known as the greatest botanists of mediaeval times. They were keen observers and discovered sexual difference between such plants as palms and hemps. They roamed about on sea shores, on mountains and in distant lands in quest of rare botanical herbs. They classified plants into those that grow from seeds, those that grow from cuttings and those that grow of their own accord, i.e., wild growth. The Spanish Muslims advanced in botany far beyond the state in which “it had been left by Dioscorides and augmented the herbology of the Greeks by the addition of 2,000 plants” Regular botanical gardens existed in Cordova, Baghdad, Cairo and Fez for teaching and experimental purposes. Some of these were the finest in the world.

The Cordovan physician, Al-Ghafiqi (D. 1165) was a renowned botanist, who collected plants in Spain and Africa, and described them most accurately. According to G. Sarton he was “the greatest expert of his time on simples. His description of plants was the most precise ever made in Islam; he gave the names of each in Arabic, Latin and Berber”. His outstanding work Al Adwiyah al Mufradah dealing with simples was later appropriated by Ibn Baytar.”

Abu Zakariya Yahya Ibn Muhammad Ibn AlAwwan, who flourished at the end of 12 century in Seville (Spain) was the author of the most important Islamic treatise on agriculture during the mediaeval times entitled Kitab al Filahah. The book treats more than 585 plants and deals with the cultivation of more than 50 fruit trees. It also discusses numerous diseases of plants and suggests their remedies. The book presents new observations on properties of soil and different types of manures.

Abdullah Ibn Ahmad Ibn al-Baytar, was the greatest botanist and pharmacist of Spain–in fact the greatest of mediaeval times. He roamed about in search of plants and collected herbs on the Mediterranean littoral, from Spain to Syria, described more than 1,400 medical drugs and compared them with the records of more than 150 ancient and Arabian authors. The collection of simple drugs composed by him is the last outstanding botanical work in Arabic. “This book, in fact is the most important for the whole period extending from Dioscorides down to the 16th century.” It is an encyclopaedic work on the subject. He later entered into the service of the Ayyubid king, al-Malik al-l(amil, as his chief herbalist in Cairo. From there he travelled through Syria and Asia Minor, and died in Damascus. One of his works AI-Mughani-fi al Adwiyah al Mufradah deals with medicine. The other Al Jami Ji al Adwiyah al Mufradah is a very valuable book containing simple remedies regarding animal, vegetable and mineral matters which have been described above. It deals also with 200 novel plants which were not known up to that time. Abul Abbas Al-Nabati also wandered along the African Coast from Spain to Arabia in search of herbs and plants. He discovered some rare plants on the shore of Red Sea.

Another botanist Ibn Sauri, was accompanied by an artist during his travels in Syria, who made sketches of the plants which they found.

Ibn Wahshiya, wrote his celebrated work al-Filahah al-Nabatiyah containing valuable information about animals and plants.

Many Cosmographical encyclopaedias have been written by Arabs and Persians, which contain sections on animals, plants and stones, of which the best known is that of Zakariya al-Kaiwini, who died in 1283 A. D. Al-Dinawari wrote an excellent ‘book of plants’ and al-Bakri has written a book describing in detail the ‘Plants of Andalusia’

Ibn Maskwaih, a contemporary of Al-Beruni, advanced a definite theory about evolution. According to him plant life at its lowest stage of evolution does not need any seed for its birth and growth. Nor does it perpetuate its species by means of the seed.

The great advancement of botanical science in Spain led to the development of agriculture and horticulture on a grand scale. “Horticulture improvements,” says G. Sarton, “constituted the finest legacies of Islam, and the gardens of Spain proclaim to this clay one of the noblest virtues of her Muslim conquerors- The development of agriculture was one of the glories of Muslim Spain.”‘

Transmission to the West

The Muslims were the pioneers of sciences and arts during mediaeval times and formed the necessary link between the ancients and the moderns. Their light of learning dispelled the gloom that had enveloped Europe. Moorish Spain was the main source from which the scientific knowledge of the Muslims and their great achievements were transmitted to France, Germany and England. The Spanish universities of Cordova, Seville and Granada were thronged with Christian and Jewish students who learnt science from the Muslim scientists and who then popularised them in their native lands. Another source for the transmission of Muslim scientific knowledge was Sicily, where during the reign of Muslim kings and even afterwards a large number of scientific works were translated from Arabic into Latin. The most prominent translators who translated Muslims works from Arabic into European languages were Gerard of Cremona, Adelard of Bath, Roger Bacon and Robert Chester.

Writing in his celebrated work Moors in Spain Stanley Lane Poole says, “For nearly eight centuries under the Mohammadan rulers, Spain set out to all Europe a shining example of a civilized and enlightened State–Arts, literature and science prospered as they prospered nowhere in Europe. Students flocked from France, Germany and England to drink from the fountain of learning which flowed down in the cities of Moors. The surgeons and doctors of Andalusia were in the van of science; women were encouraged to serious study and the lady doctor was not always unknown among the people of Cordova. Mathematics, astronomy and botany, history, philosophy and jurisprudence, were to be mastered in Spain, and Spain alone. The practical work of the field, the scientific methods of irrigation, the arts of fortification and shipbuilding, of the highest and most elaborate products of the loom, the gravel and the hammer, the potter’s wheel and mason’s trowel, were brought to perfection by the Spanish Moors. Whatever makes a kingdom great and prosperous, whatever tends to refinement and civilization was found in Muslim Spain.”

The students flocked to Spanish cities from all parts of Europe to be infused with the light of learning which lit up Moorish Spain. Another western historian writes, “The light of these universities shone far beyond the Muslim world, and drew students to them from east and west. At Cordova, in particular, there were a number of Christian students, and the influence of Arab philosophy coming by way of Spain upon universities of Paris, Oxford and North Italy and upon Western Europe thought generally, was very considerable indeed. The book copying industry flourished at Alexandria, Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad and about the year 970, there were 27 free schools open in Cordova for the education of the poor.

Such were the great achievements of Muslims in the field of science which paved the way for the growth of modern sciences.

Copied from ‘THE ISLAMIC SCHOLAR’, to purchase the CD ROM please go to:

http://www.parexcellence.co.za/

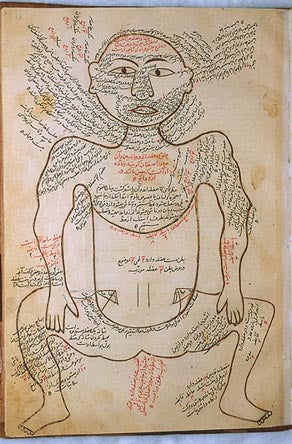

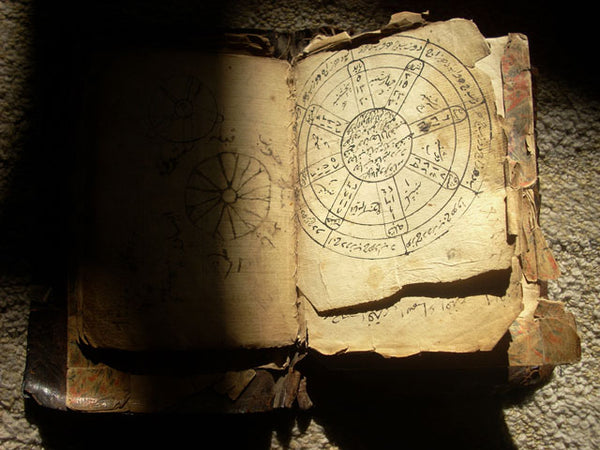

The image used in this article is taken from Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine, go to:

ttp://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/catalog_tb.html

7 Responses

: <a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences </a>

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

Departement of Sharia

Departamento de Sharia

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/

<a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Departement of Sharia </a>

A very useful post. I truly thank you for the information contained in this article.

: <a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences </a>

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

Departement of Sharia

Departamento de Sharia

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/

: <a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences </a>

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/

: <a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences </a>

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/

CRIST

MUSLIM NEVER WANT TO CONTRIBUTE,

AND NO KNOLEGE ABOUT ISCIENCE, THEN HOW THEY CAN CONTRIBUTE,

MUSLIM IS NOTHING EXEPT A DANGEROUS ANIMAL ON THE EARTH, THEY SHOULD BE EXTINCT FROM EARTH.

THEY CAN ONLY CONTRIBUTE IN INCREASING POPULATION.

Leave a comment

Also in SCIENCE & MEDICINE

Revolution by the Ream

Paper, one of the most ubiquitous materials in modern life, was invented in China more than 2000 years ago. Nearly a millennium passed, however, before Europeans first used it, and they only began to manufacture it in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Muslims had established the first paper mills in Spain. The German Ulman Stromer, who had seen paper mills in Italy, built the first one north of the Alps at Nuremberg in the late 14th century.

The cultural revolution begun by Johann Gutenberg's printing press in 15th-century Mainz could not have taken place without paper mills like Stromer's, for even the earliest printing presses produced books at many times the speed of hand copyists, and had to be fed with reams and reams of paper. Our demand for paper has never been satisfied since, for we constantly develop new uses for this versatile material and new sources for the fiber from which it is made. Even today, despite the computer's promise to provide us with "paperless offices," we all use more paper than ever before, not only for communication but also for wrapping, filtering, construction and hundreds of other purposes.

Scientific Inventions by Muslims

Inventions

Abul Hasan is distinguished as the inventor of the Telescope, which he described to be a Tube, to the extremities of which were attached diopters”.

The Great Explorers of Islam

It was an Arab caravan which brought Hazrat Yusuf (Prophet Joseph) to Egypt. Moreover, the fertile areas in Arabia including Yemen, Yamama, Oman, Bahrein and Hadari-Maut were situated on the coast, and the Arabs being sea-faring people took sea routes in order to reach these places and fulfilling their commercial ventures.

<a href="https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/">Departement of Sharia </a>

February 17, 2026

A very useful post. I truly thank you for the information contained in this article.

Departement of Sharia

Departamento de Sharia

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/