Artist Profile: a Picture of Learning

Jan 2014 -By Leonard Stall (Vision Magazine)

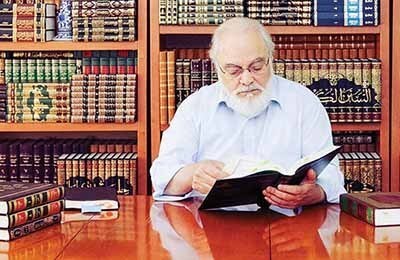

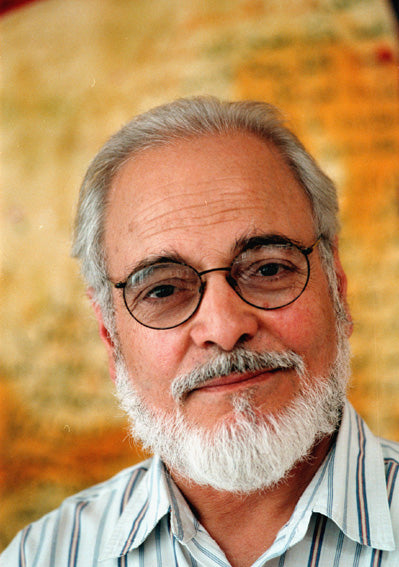

Every one of my visits to the leafy home of the man widely considered one of the world’s greatest living Arabic artists, Ali Omar Ermes, reveals a new aspect of the painter and his work, but one thing is clear from the start: he is a thinker and an intellectual, as much as a gifted artist.

Each painting in his studio, or which I find offered at an international auction, or displayed in the leading museums and influential private collections around the world, has been borne of painstaking research and academic rigour. Ermes’ work is always beautiful and engaging, and has a distinct style using Arabic letter script and poetry. But alongside the beauty of the painting, the artworks lure you in and invite consideration of a subject through the eyes of a deeply religious and sensitive soul, a champion of Islamic thought, science and heritage, of Arabic language and culture.

The approach has been the same throughout Ermes’ career, which began almost 50 years ago when he was a student in the UK, a country that became home as he was unable to live under the Gaddafi regime in his beloved Middle-Eastern birthplace, Libya. Today, he lives in the Surrey greenbelt on the outskirts of London, and he proves a charming and engaging host. Every wall in his home is crammed with books. The subject matter is revealing of the man and the spirit of his work. Much of it is Arabic literature and Qur’anic reference material, poetry and history. But there are English language history books and religious and cultural references. It is a house of learning and the learned, and not a library ‘for show’.

There are piles of books in use, and articles covered in notes. But there is order, too. The library is impeccable. Everything has a place, and is there for a reason. It is the same in Ermes’ garden studio, and in his art, where magnetic colour, letterforms, image and size are steeped in the academic rigour, deep thought and an intelligence that informs and inspires every final artwork. His work is precise and deliberate, and it speaks to viewers, opens a conversation, and a door of thought for interpretations. Collectively these works are bridge-builders between cultures, passing on ideas and traditions and delivering an underlying message of human responsibility, peace and welfare.

The striking impact [of his art] allows him to communicate directly with people from other traditions and faiths, suggesting to them how much they have in common with the Arabic and Islamic lands.

The curator of Islamic Collections at the British Museum

“My artworks are like reference books,” the artist tells me. “I hope they are an inspiration, and introduce new ideas.” This is surely the reason for Ermes’ enduring popularity in the Islamic and art worlds. And it explains why his art is so widely collected by museums – from the British Museum to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, the National Museum of African Art to the Ashmolean in Oxford, by the National Galleries of Jordan and Malaysia, and by sheikhs, royalty and embassies around the world.

His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE, and Ruler of Dubai, admired Fetal Fityan (2003), featured on the cover of the Prime Minister’s Office Arabic Language Commission Report. His Highness Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum owns Ba Ayoon el-Akhbar (1992), and, of late, His Highness Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed Al Maktoum, Chairman of Dubai Expo 2020, received a special artwork for the event, Tawasul Al-Himam – already affectionately known as “The Expo painting”.

As Ermes’ work continues to win plaudits and exposure to an ever wider audience, it seems clear that his place among the greats of Arabic art is assured for a considerable time to come.

Leave a comment

Also in NEWS

Tributes paid to leading Arab artist, Ali Omar Ermes

Ali Omar Ermes’ Recent Works to Be Exhibited at Meem Gallery - 10 DECEMBER 2010 - 27 JANUARY 2011