The World of Islam – Its Art

Written by John Sabini

Photographed by Peter Keen

As the Festival of Islam proves, the arts of Islam show a surprising unity through the ages and across the wide vistas of the Islamic world. Although there are certainly individual differences, and even exceptions, it is easy to recognize the common elements.

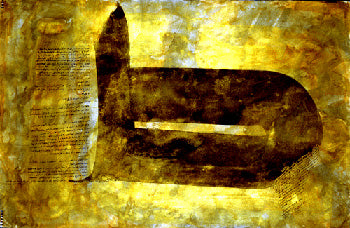

Essentially, Islamic art is abstract—an art of patterns, symmetrical, two-dimensional, repetitive and infinitely extendable. Even when natural forms are used they are so stylized as to be virtual abstractions. The arabesque, for example, is based on vegetal forms but has a logic of its own and does not seek to reproduce the logic of growing things. Pure geometry is a strong element of design, mixing the curvilinear with the rectilinear. Another important element is calligraphy—Arabic writing—usually a quotation from the Koran and often drawn or carved in such complex ways as to be almost illegible. Color is also important, although rarely used realistically. Illusion is not an aim; stone or wood, paint or ceramic is not intended to represent actual bodies or leaves or animal forms but only to suggest an ideal. Pushed to the periphery of Islamic art, and never used in a religious context, is representation of the human form.

All this makes it difficult for a Westerner to understand and appreciate Islamic art. For until the advent of modern art, the artistic values in the West leaned toward illusion, especially the illusion of three-dimensional space, the direct copying of nature, the historical, mythical or religious anecdote and, above all, the human form and face, the subject of the West's greatest works of art. In the absence of those touchstones, the Westerner tends to equate Islamic art with mere decoration and thus place it on a par with what we consider to be the minor or "applied" arts of the West. But this attitude betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of Islamic art, which has its own hierarchy of values. In this hierarchy, calligraphy comes first—because of its holy association with the Word of God—and the human form comes last because of religious strictures.

Actually, the very limitations of Islamic art are its strength. Freed from the necessity of representing nature, the Muslim artist is able to devote himself with passionate intensity to the development of the two-dimensional and the abstract. As Swiss Muslim convert Titus Burckhardt put it, in the Festival book Art of Islam, the absence of images creates "the quite silent exteriorization, as it were, of a contemplative state..." And the proliferation of decoration, he continues, "does not contradict this quality of contemplative emptiness; on the contrary, ornamentation with abstract forms enhances it through its unbroken rhythm and its endless interweaving."

The limitations, moreover, were deliberate, not accidental. As Islam expanded, it absorbed or touched numerous cultures with quite different and sometimes sophisticated artistic developments. And although some of those alien influences were accepted and absorbed, others—such as portrayal of the human form, sculpture in the round and mural painting—were rejected. All the new influences, moreover, were soon swallowed up in an Islamic style that was distinctive and, eventually, homogeneous.

There were many reasons for this homogeneity. The basic reason was the monolithic character of Islam itself. Another was the unifying impact of the Arabic language. Other factors were the unusual mobility within the Islamic world and the international character of its trade—both insuring the spread of identical ideas, techniques and motifs.

There were also purely artistic and technical reasons for the unity of style. The artists were largely anonymous, not intent on creating original masterpieces but products of high quality within a continuing tradition. There was no distinction between crafts and fine arts, nor between sacred and secular art, so that styles and techniques were freely transferred from the mosque to the palace and even to the public baths. They were also readily transferred from one medium to another, so that a pattern originating in the weaving of textiles was frequently translated into wood, metal or stone—as, again, displays at the Festival show. Moreover, the artistic tradition was so strong that non-Muslim artists—Eastern Christians, Armenians, Jews—were content to work within it.

Above all, there was the spirit of Islam itself: the emphasis on the Oneness of God, the congruence of knowledge, the brotherhood of man. As Burckhardt says, Islamic art is essentially the projection into the visual order of certain aspects of, or dimensions of, Divine Unity—a unity that is expressed in the visible world by the harmony of geometry and rhythm.

One aspect of Islamic art that the Western mind could not, and did not, dismiss as decoration is architecture. Anyone's list of the ten most beautiful buildings in the world would, unquestionably, include one or two examples from the World of Islam—the Alhambra in Spain, perhaps, the Taj Mahal in India, or the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

None of these, of course, could be shown at the Festival. Nevertheless, the audiovisual display in the unusual cube theater at the Hayward Gallery captured the central importance of architecture throughout the Islamic world in providing a place of worship, prayer, sanctuary and study—the mosque—and also a setting for the allied artistic achievements in carpentry, masonry, carving, stucco and marble work.

The first mosque was the house of the Prophet in Medina, a rectangular courtyard with a roofed area at one end in which the Prophet's Companions could meet and a covered passage at the opposite end for added shelter. Since then there have been some simple additions to the structure to meet liturgical requirements: a hall to accommodate worshippers, with perhaps a courtyard for the overflow; a mihrab or niche positioned to indicate the direction of prayer toward Mecca; a minbar, a flight of steps from which the Friday sermon is preached; facilities for the ritual washing required before prayer; and perhaps a minaret or other high place—the roof will do—from which the call to prayer can be heard throughout the community.

From those beginnings have come the examples of Islamic architecture projected so vividly in the Hayward Gallery: the eighth-century Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, a glorified replica of Muhammad's house in Medina, but greatly enlarged and embellished with arched porticos and a dome, the whole clothed in marble, stone and gold-backed mosaics; the ninth-century Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, with a forest of columns in a whitewashed prayer hall and a courtyard so vast it seems to reflect the surrounding desert; the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Spain and the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, the former rendered weightless by the superimposed arches, the latter looking like a fortress with its crenellated walls and spiral minaret like a watch tower.

Some mosques, of course, reflect forms found in other cultures and adopted by Islam. In Persia, for example, builders typically used forms going back to Sasanid times and earlier—forms such as the striking iwan, a high semicircular vault open on one side, like a gigantic niche. In Ottoman Turkey, where Islam inherited the impressive domed churches of Byzantium, architects adopted the central dome over a rectangular base, often surrounded by subsidiary domes; indeed the great Ottoman architect Sinan constructed a dome for the Mosque of Sultan Selim that exceeded the measurements of the Hagia Sophia itself.

One element of a mosque that betrays ethnic origins is the minaret, the most distinctive feature in its silhouette. Although not a liturgical requirement, the minaret can be a thing of great beauty and architects everywhere seemed glad to meet the challenge. Minarets in Spain and North Africa are usually square; those in Turkey round, with conical caps; and those in Egypt often composite. There are also some in India which are octagonal and capped with domes.

Because of the great beauty of many mosques, Westerners tend to forget that many of the greatest Islamic buildings are not mosques, but some other form of religious or secular architecture. The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem—the oldest completely preserved Islamic building—is a sanctuary built over the rock on which Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son and to which Muhammad is believed to have been carried during his "Night Journey" (See Aramco World, July-Aug., 1974). The Alhambra (Aramco World, May-June, 1967) in Granada is a palace, built, it seems, of light, and the Taj Mahal is the mausoleum of the beloved wife of the Mogul emperor Shah Jahan (Aramco World, July-Aug., 1968). All are different, but all are magnificent.

Another aspect of Islamic art familiar to the West is weaving. As long ago as the Middle Ages, Europe discovered the beauty of Islamic textiles and for many centuries the looms of Islam supplied the world with cotton, muslin, damask and gauze.

In the Islamic nations themselves, textiles took the place of furniture in the form of rugs and cushions, hangings and canopies. And, as they could be easily transported from country to country, patterns and techniques achieved such a similarity that even experts cannot always tell whether a piece of cloth originated in Baghdad or Cordoba, Damascus or Palermo. The designs in textiles—two-dimensional, symmetrical and repetitive in character—in turn affected the other arts, especially architecture, where tiles and mosaics imitated the effect of rugs and tapestries on floors and walls, and even the art of the book, with pages often laid out with borders and field of intricate patterns like an Oriental rug.

The knotted carpet is, of course, the supreme example of Islamic textile art. It is thought to be of nomad origin, for the raw material—the hair of sheep and goats—is the major product of Bedouin economy, and even the dyes originally used were made from wild plants found in out-of-the-way places. Later, certainly, Persian carpets came to be the best known Oriental carpet, but in fact fine carpets were also made in Egypt, Turkey, the Caucasus, Afghanistan and India.

Ceramics, in the form of pottery or tiles, were also a Western import from the Islamic world. Imports began as early as the 13th century and were widely copied thereafter in the West. Many of the pottery making techniques were inherited from the older civilizations of the Middle East and Islamic potters also learned about glazes from Chinese imports. But they invented many of their own techniques; one of the most successful was lustre painting, which gave a metallic sheen resembling bronze or gold. Islam also, as in other arts, stylized animal and vegetable designs and soon saw that arabesque and calligraphy were perfectly adapted to the curved surfaces of bowls and jugs.

Tiles, a very ancient Middle Eastern device for protecting and decorating mud-brick walls, were a refined art in the Islamic world. They turned buildings into shimmering tents and canopies without apparent weight or substance, particularly in Persia and Central Asia. Koranic inscriptions in raised tiles decorated walls and domes.

As with ceramics, Muslim artists learned many of their techniques of glass making, metal engraving and inlay, wood and stone carving, and ivory working from their historical predecessors. But—again by the designs of arabesque, geometry, and calligraphy—they soon turned them into Islamic arts.

A less familiar art form prominently featured at the Festival is miniature painting, which reached a high degree of artistic development in Persia, Turkey and Mogul India. A purely secular art, it was also essentially private, confined to the pages of books and albums where it illustrated poems and tales, or sometimes scientific works on astronomy and natural history. Yet it too partook of the nature of Islamic art. The miniaturists were usually calligraphers as well, and their work was intimately linked with the written word. As in other arts at the Festival, the paintings are two-dimensional, concerned more with pattern than with reality, conceptual rather than realistic and rendered in colors that are bright and decorative but unnatural.

Miniature painting, as displayed at the Festival, recaptured still another Islamic art form: gardens. Gardens in the Koran are an image of paradise. As water, shade and flowering plants are precious boons in harsh and arid countries, it is little wonder that the art of gardens flourished in the Islamic world, or that they were depicted in miniatures and tiles and described in poetry and manuals. The classical gardens—with a few exceptions such as those near Spain's Alhambra—have disappeared, but it is clear from the miniatures that they too shared the elements of other Islamic arts. They were geometrical in form but lush in details, reflecting the multiplicity in unity that was the mark of the World of Islam itself and its Festival in London.

This article appeared on pages 14-18 of the May/June 1976 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Leave a comment

Also in ART & CULTURE

2e Édition De Fikra “la Créativité Est Le Pilier De L’entrepreneuriat”

Vincenzo Nesci, l’un des principaux promoteurs de la 2e édition Fikra, lors de cette conférence internationale a abordé «la création d’entreprise et l’entrepreneuriat». Selon le directeur exécutif de Djezzy, ces derniers, «doivent être réalisés dans des conditions d’optimisme et de créativité pour permettre un réel essor dans les domaines commercial, industriel et créatif»